Naturescaping Blog

Home » Naturescaping Blog

Flying Trillium Gardens and Preserve was founded to promote ecological gardening and the conservation of Northeast native plants. Naturescaping blog is written by Kate Brittenham with photos by Kate and Carolyn.

Naturescaping

Winter Gardening: Native Shrubs and Trees for Winter Interest

By Kate Brittenham

Though the ground may be frozen (and if you are lucky, covered with a picturesque blanket of snow), there can still be interest in our gardens, both for us and for wildlife. We have compiled a sample list of native shrubs and trees that should be recognized for their beauty even in the dead of winter. There are so many more, but we had to limit ourselves!

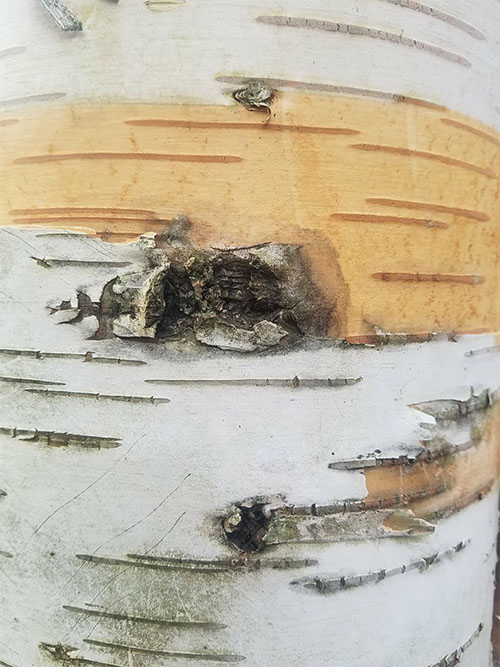

Betula papyrifera (Paperbark Birch)

Betula papyrifera (Paperbark Birch)

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

Excerpt from Birches by Robert Frost

Growing up, Betula papyrifera (Paperbark Birch) was one of my absolute favorite trees, because it created the best props for an uninhibited imagination. The peeling bark became the paper for my secret messages or ancient treasure maps. It was bracelets and necklaces or dinner plates. The options were limitless! I remember one children’s book in particular that I grew up with—The Rough-Faced Girl—an Algonquin take on the Cinderella story, where the heroin actually makes a dress out of birchbark.

As an adult, I still have a great appreciation for the beautiful bark of this tree. Incredibly easy to identify due to its peeling, papery bark, Betula papyrifera enhances the winter landscape. Use it as an accent tree or in a mass, it will stand out regardless. An allee of these trees easily creates a winter wonderland. Place it against a backdrop of evergreens, or pair it with shrubs like Ilex verticillata or Swida sericea that will pop against the pearly white bark.

Rhus typhina (Staghorn Sumac)

A very underrated shrub and frequently dismissed as a landscape plant, probably due to its “weedy” character and atypical appearance, Rhus typhina might not look like your typical garden plant, but the shrub provides valuable habitat for songbirds, who feed on its seedheads. It is named for the small hairs that grow along the younger branches, creating a fuzzy texture, not unlike the “velvet” on the horns of a stag.

A very underrated shrub and frequently dismissed as a landscape plant, probably due to its “weedy” character and atypical appearance, Rhus typhina might not look like your typical garden plant, but the shrub provides valuable habitat for songbirds, who feed on its seedheads. It is named for the small hairs that grow along the younger branches, creating a fuzzy texture, not unlike the “velvet” on the horns of a stag.

It is listed here for the unique red conical fruit, which stands out in stark contrast in the wintery landscape. Throughout the season, Rhus typhina is foliated by large, long, and pinnately shaped leaves, which turn to a nice red in the fall, but drop with the temperature. What is left through the winter season are the fruits, which make for great dried and fresh arrangements.

Largest of the North American sumacs, Rhus typhina typically grows 15-20’ in height. It will spread and form stands, making it an excellent choice to create groves or thickets in the landscape.

Hydrangea quercifolia (Oakleaf Hydrangea)

I will begin this section with a disclaimer: I have never been a fan of hydrangeas. I always thought they were too 1960s suburbia, until I began working with plants and it was this particular species, the Oak Leaf Hydrangea, that first brought me around. The moment I truly recognized their beauty was during a trip to the New York Botanical Garden in early spring, when very little was awake. The bark of Hydrangea quercifolia was absolutely striking at this point in the season and I was forever after a convert.

I will begin this section with a disclaimer: I have never been a fan of hydrangeas. I always thought they were too 1960s suburbia, until I began working with plants and it was this particular species, the Oak Leaf Hydrangea, that first brought me around. The moment I truly recognized their beauty was during a trip to the New York Botanical Garden in early spring, when very little was awake. The bark of Hydrangea quercifolia was absolutely striking at this point in the season and I was forever after a convert.

Hydrangea quercifolia is an absolutely fantastic landscape plant that has really gained in popularity in recent years, due to its versatility and seasonal interest: a great filler shrub, spreading up to 6-8ft in width and height, it is drought tolerant once established, and performs in part shade as well as full sun. Low maintenance and deer resistant, Hydrangea quercifolia produces lovely late season blooms, and the characteristic oak-shaped leaves change to a lovely red or deep purple in the autumn, as shown above.

Hydrangea quercifolia is an absolutely fantastic landscape plant that has really gained in popularity in recent years, due to its versatility and seasonal interest: a great filler shrub, spreading up to 6-8ft in width and height, it is drought tolerant once established, and performs in part shade as well as full sun. Low maintenance and deer resistant, Hydrangea quercifolia produces lovely late season blooms, and the characteristic oak-shaped leaves change to a lovely red or deep purple in the autumn, as shown above.

In the early winter, the blooms will remain dried on the stalks, and make for excellent additions to a dried flower arrangement. The pale brown and beige bark provides interest throughout the winter, peeling in layers similar to Betula papyrifera, and is truly beautiful against the snow. There are many cultivars and ‘Snow Queen’ in particular is a great option for even more distinct bark coloration and peeling. Pictured above is the straight species.

Swida sericea (Red Osier or Red-Twig Dogwood)

This is a plant meant for the winter landscape. A thicket-forming shrub, it creates horizons of red wherever it grows and does well in a variety of conditions. I have seen it happily established along the slopes of medians on I-87 in upstate New York, but it is happiest in moist to wet soils, like marshes and wetlands. An erosion stabilizer, it is also a great rain garden plant. Best grown in masses, and pairs well with grasses and perennials with grass-like foliage, like Amsonia hubrichtii and tabernaemontana—particularly in the fall and winter. It also pairs well with evergreens like Ilex opaca for a bit of that holiday color.

This is a plant meant for the winter landscape. A thicket-forming shrub, it creates horizons of red wherever it grows and does well in a variety of conditions. I have seen it happily established along the slopes of medians on I-87 in upstate New York, but it is happiest in moist to wet soils, like marshes and wetlands. An erosion stabilizer, it is also a great rain garden plant. Best grown in masses, and pairs well with grasses and perennials with grass-like foliage, like Amsonia hubrichtii and tabernaemontana—particularly in the fall and winter. It also pairs well with evergreens like Ilex opaca for a bit of that holiday color.

A host for the larvae of the Spring Azure (Celastrina ladon) butterfly, in the late spring, the small flowers attract pollinators and later, turn to berries that the birds love. The berries have high nutritional value and ripen just around the time that the birds migrate. Still not convinced of its landscaping value? For those of you who live in deer-inundated areas, Swida sericea is deer resistant—although not deer proof (very few plants truly are).

A little bit of fun history: the twigs have historically been used in baskets, which I can imagine would be beautiful with that red color, assuming it lasts. (As the plants age, older twigs become brown; judicious pruning renews red stems.) The common name “osier” comes from the name given to willow twigs that were used to create baskets.

Ilex verticillata (Winterberry)

Without fail, the top plant for winter interest, in my opinion, is Ilex verticillata. When anyone asks me for winter interest, this beautiful plant immediately comes to mind. For most of the growing season, it is a relatively understated background shrub, with a nice shape and lovely foliage, but nothing striking. Its true landscape purpose emerges in late fall and early winter, when the leaves fall and the bright red berries (a favorite of songbirds) become visible. Commonly used in holiday decorations and arrangements, popular among floral designers, Ilex verticillata is a requisite for the winter garden.

Without fail, the top plant for winter interest, in my opinion, is Ilex verticillata. When anyone asks me for winter interest, this beautiful plant immediately comes to mind. For most of the growing season, it is a relatively understated background shrub, with a nice shape and lovely foliage, but nothing striking. Its true landscape purpose emerges in late fall and early winter, when the leaves fall and the bright red berries (a favorite of songbirds) become visible. Commonly used in holiday decorations and arrangements, popular among floral designers, Ilex verticillata is a requisite for the winter garden.

In the wild, Ilex verticillata can grow quite tall, to about the height of a small tree, however there are many dwarf varieties available on the market. One lovely (and easy to find) dwarf cultivar is ‘Red Sprite’. It is important to note that, like all hollies, Ilex verticillata is dioecious, meaning that the flowers on one shrub will be all female, and all male on another. In other words, in order to get those beautiful berries, both male and female shrubs are necessary. A good male cultivar that will pollinate happily ‘Red Sprite’ is the ‘Southern Gentleman’ cultivar. For larger sized shrubs, both ‘Winter Red’ and ‘Jolly Red’ produce bountiful berry-laden branches.

In the wild, Ilex verticillata can grow quite tall, to about the height of a small tree, however there are many dwarf varieties available on the market. One lovely (and easy to find) dwarf cultivar is ‘Red Sprite’. It is important to note that, like all hollies, Ilex verticillata is dioecious, meaning that the flowers on one shrub will be all female, and all male on another. In other words, in order to get those beautiful berries, both male and female shrubs are necessary. A good male cultivar that will pollinate happily ‘Red Sprite’ is the ‘Southern Gentleman’ cultivar. For larger sized shrubs, both ‘Winter Red’ and ‘Jolly Red’ produce bountiful berry-laden branches.

Ilex opaca (American Holly)

I have heard that many people hold the opinion that the American Holly is not as nice as the English, but I personally do not understand that perception. I think to the untrained eye, they are nearly indistinguishable, and Ilex opaca provides a marvelous substitute for the English. Its classic spikes, green color and vibrant berries evoke the spirit of the winter season. It is also deer resistant—you would have to be incredible hungry to tangle with those spiky leaves.

I have heard that many people hold the opinion that the American Holly is not as nice as the English, but I personally do not understand that perception. I think to the untrained eye, they are nearly indistinguishable, and Ilex opaca provides a marvelous substitute for the English. Its classic spikes, green color and vibrant berries evoke the spirit of the winter season. It is also deer resistant—you would have to be incredible hungry to tangle with those spiky leaves.

Ilex opaca is considered a shrub, but will grow quite tall and in a pyramidal shape. It can be trained to stay low but there are also cultivars such as ‘Maryland Dwarf’ and ‘Clarendon Spreading’ that are natural dwarves. Ilex opaca can also be pruned into a hedge-shape. Again, as an Ilex, the American Holly requires both male and female plants in order to produce berries. Put it in full sun or part shade, it will happily grow in either condition.

Favorite Fall Plants

By Kate Brittenham

As the leaves slowly start to turn, we are reminded that despite the warm weather we’ve been having in New York, it is in fact the end of summer, and autumn is right around the corner. If you are like me, you are bewildered by this realization, wondering where the summer went! This season, as opposed to others, particularly felt very quick to me.

But now I can feel the pace slowing, and since Starbucks has officially put pumpkin spice latte back on the menu, autumn feels inevitable. Fortunately, autumn in the Northeast is typically spectacular—infamously so. For those of us who live here, fall is a special treat, and one I always look forward to, so in honor of the changing seasons, we thought we’d profile some of our absolute favorites for autumn interest, that you could incorporate into your gardens and landscape to get some of that spectacular color.

I love Goldenrod too much to pick just one species to talk about. Goldenrod has gotten a bad reputation, being confused frequently with ragweed, which causes hayfever, however Goldenrod is not wind pollinated, and therefore does not cause allergies. A very drought-tolerant plant, that iconic golden color always brings back memories of my childhood roaming the former dairy pastures of upstate New York. You can hardly go wrong with any species, and all of them are fantastic pollinator plants.

Some even do well in shade, like Solidago flexuosa, the Zigzag goldenrod, and S. caesia, the Blue-stemmed or Wreath goldenrod. They will also do well in full sun, given adequate moisture. Some, such as Solidago bicolor, silverrod, the white species, are great for dry areas. It has a lovely, candle-like single stem. Solidago nemoralis (Gray goldenrod), is one of the smaller species, and does well in very tough sites with poor, rocky or sandy soils. There is even a goldenrod for places that get hit by salt frequently (such as road salt in the winter), like Solidago sempervirens (Seaside goldenrod), which grows in the wild in coastal locations.

I think any meadow should be sure to include Goldenrod for that fantastic autumn color and pollinator value. Some of the best individual species for the meadow are Solidago speciosa (Showy goldenrod), S. canadensis (Canadian goldenrod), S. rugosa (Rough goldenrod), S. odora (Aromatic goldenrod), and S. rigida (Stiff goldenrod). Some species can be aggressive—Solidago canadensis and S. rugosa, for example, but when planted with similarly aggressive plants (like some grasses and other Solidago species), they can be kept in check with regular mowing.

Parthenocissus quinquefolius gets a bad rap for strangling trees—I am not entirely certain where this has come from, but it may be influenced by the invasion of vines like Asian Bittersweet, which do wreak havoc on our forests. Parthenocissus does not behave like Bittersweet—while it may be found climbing up trunks and branches, it does not harm those trees. So feel fine planting this fall stunner in your backyard, on your fire escape—just about anywhere. Parthenocissus is an incredibly adaptable plant and has a wide variety of fall color from brilliant fire red (shown above on arbor), or a deep purple that complements the blue berries birds love (shown below). Plant Parthenocissus on a wall, fence, arbor or exposed stones for a brilliant autumnal display.

Eragrostis spectabilis is a very surprising grass. For the majority of the season, it is not much to look at, then suddenly, around late summer, it releases its seedheads producing this stunning purple cloud through the fall. It is a low, mounding grass that will not get very high—subsequently, I find that it makes great borders. It also does well designed as swaths of color placed in the distance, mixed in with other perennials and grasses in landscapes. It is especially useful as a meadow plant, if the desired meadow height is below 2 feet in height or as an edging for taller meadows.

Very drought tolerant, it prefers well-drained soils, but will do well in a formal garden setting. Below, a border of Eragrostis frames a perennial border in a suburban front yard in upstate New York, just outside Albany, NY.

Another unique fall interest plant, and an all around favorite of mine, is Schizachyrium scoparium, or Little Bluestem. A fantastic species, Schizachyrium does prefer well-drained, drier soils, but is very adaptable, so long as it has adequate drainage. As opposed to Andropogon gerardii (Big Bluestem), Schizachyrium will not get very tall. And with so many cultivars to choose from, the color possibilities are pretty much unlimited. Some of the more exciting cultivars include S. scoparium ‘The Blues’, S. scoparium ‘Standing Ovation’, S. scoparium ‘Prairie Munchkin’ (a dwarf variety), S. scoparium ‘Carousel’, and S. scoparium ‘Smoke Signals.’

It should be said, however, that the straight species itself has so much variation that cultivars are almost unnecessary. I have driven past multiple stands on the Taconic Parkway in New York State, where one population might have a slight bluish hue and then 5 miles down the road there is another more purple population and then 5 miles past that there yet another more red population!

And for the finale: Acer saccharum, or the Sugar Maple:

Nothing is more iconic about the Northeast as the fall, and nothing contributes more to that than Acer saccharum. It lights up the forest, heralding the arrival of winter and the promise of maple syrup to be tapped, only a few months later. While not the only tree that can be tapped, it has a high sugar content, making it the most popular species for that purpose. And of course, nothing beats this tree for fall color. A great specimen tree as an individual, the color also looks great in a mass.

Purple Pollinator Power: Cercis Canadensis, The Eastern Redbud

by Kate Brittenham

I suffer from DWB these days—Driving While Botanizing. How many of you can relate? I am positive it is endemic amongst plant lovers. The things that catch my eye this time of year are most definitely the early blooming trees. Most of these bloom in shades of white and pink, but there is one that stands out from the crowd: the eastern redbud. And this week in particular seems to be peak season in the lower Hudson Valley.

A subtle but stunning tree, the redbud, or Cercis canadensis, will not reach great heights. An understory tree, its purple-pink flowers make it a statement in the landscape, and it has been wholeheartedly embraced by the nursery and horticulture industry for its ornamental umph. Its short stature makes it an excellent street tree and you will easily spot it this time of year in many plantings alongside public roadways. While there is a non-native redbud, Cercis chinensis, it is very easy to distinguish from the indigenous variety; Cercis canadensis is a tree, and has a single trunk, while Cercis chinensis is a shrub and has multiple branching stems.

The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center states that there are three varieties of Cercis canadensis: Cercis canadensis var. canadensis, Cercis canadensis var. texensis and Cercis canadensis var. Mexicana—something I was unaware of until doing my research. The latter is found in Mexico and parts of western Texas; C. canadensis var. texensis is indigenous to the geographic region found between Texas, south of Oklahoma, and northern Mexico; and the variety canadensis is indigenous to our region, though its range extends all the way down to Texas as well.

Cercis canadensis in flower. Taken at the New York Botanical Garden.

Photo: Kate Brittenham

It is a member of the Fabaceae (Pea) family, which is made abundantly clear by looking at the flowers, which resemble many of those in its family. Up close, Cercis canadensis’ flowers can look like alien growths growing on tree bark. The flowers can form directly off of the bark, not off any long stems or branches, thus giving it this “fungal, growth-like” appearance. In the summer, it produces beautiful, waxy heart-shaped leaves. Besides its seasonal interest, Cercis canadensis is a great plant for both sunlight and shade, proving itself adaptable to both light conditions.

Cercis canadensis in a shaded woodland, with a pollinator friend.

Photo: Carolyn Summers.

Additionally, Cercis canadensis is a fantastic pollinator. Typically blooming from March until May, Cercis canadensis is one of those important early pollinator plants. According to the Xerces Society, it holds particular value to native long-tongued bees who are attracted to its nectar and pollen. The tree also plays host to butterfly caterpillars and other insect larvae who munch on its leaves.

A fantastic substitute for non-native cherry trees—for which it is often mistaken—Cercis canadensis is truly an impressive tree in the landscape, a real show-stopper in the early spring in any garden. But more importantly, it provides an important ecological service for our pollinators.

Resources:

Pollinator Plants: Mid-Atlantic Region. Xerces Society. July 2015. <http://www.xerces.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MidAtlanticPlantList_web.pdf>

“Redbud. Cercis canadensis. Senna family (Caesalpiniaceae).” Illinoiswildflowers.com. <http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/trees/plants/redbud.htm>

“Cercis canadensis.” December 2015. Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. <http://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=ceca4>

Cardamine diphylla (Toothwort)

By Kate Brittenham

When we first began putting together this list of pollinator-friendly plants, we wanted to include species that are less well known, and could use a moment in the spotlight. Cardamine diphylla (Toothwort) is one such plant. Native to Northeastern woodlands, it blooms from March to June, a sweet, delicate bell-like white flower which attracts early pollinators such as long-tongued bees and flies. This plant itself typically doesn’t get much higher than 16”, but it has a clonal characteristic, forming colonies.

In addition to providing early season nectar, Cardamine plays host to Pieris virginiensis (West Virginia White), a butterfly commonly mistaken for the common cabbage white, which lays its eggs on the plant’s leaves. The invasive plant garlic mustard will sometimes fool the butterfly into laying eggs on its leaves instead, as both plants are members of the Mustard Family. But although distantly related, the caterpillars of the West Virginia White cannot digest the leaves of garlic mustard, and perish. The proliferation of invasive garlic mustard may be one reason the West Virginia White is becoming scarce. Perhaps planting its host plants, like Cardamine and other native mustards, will encourage its survival.

There appears to be a common misconception that if a plant is not found in bright, sunny meadows, it is not a pollinator plant. Cardamine is just one plant that demonstrates how untrue that is. We chose Cardamine, not only to bring attention to a plant that is not commonly associated with pollinators, but also to show that even if you have a shady, wooded area, you can still provide habitat for pollinators.

Remember, pollinators have been here for many, many, years developing plant relationships. It should come as no surprise that they have not limited themselves solely to the open, sunny meadows. So if you have a shade garden, rest assured that you can incorporate pollinator-friendly plants such as Cardamine diphylla. While not a common plant at nurseries, there are some that do provide it for sale, such as Edge of the Woods Nursery in PA. Consider doing a quick search with local nurseries—some of them may never have heard of it, but consumer demand is a powerful thing. If more nurseries hear that people desire plants they do not stock, they may become interested in carrying those species.

Photos courtesy of Carolyn Summers.

Here’s To The Pollinators!

Backyard Politics: Creating Gardens of Impact and Change

Kate Brittenham

As we begin preparing for the spring, excitedly scrolling through plant availability lists from our favorite nurseries and planning trips to the local garden center, we should take this season to look to our gardens as symbols of change and impact. With the current political climate in Washington, you may be feeling a little helpless, but there is one thing that we can do with our gardens this year to have a real impact on the world around us.

Let’s talk about the pollinators—those organisms with whom we are ecologically intricately linked, but who we now find imperiled. With habitat vanishing due to development and the introduction of pesticides which have devastating impacts on specific species, pollinators are under duress. To bring attention to the plight of pollinators like bees, flies, butterflies, birds, the Association for Garden Communicators (GWA) has partnered with the National Pollinator Garden Network to promote their initiative: the Million Garden Pollinator Challenge. The goal of the initiative is to “increase nectar- and pollen-providing landscapes” in order to counteract the decrease in habitat. The ultimate intent of the Challenge is to “promote and count 1 million pollinator forage locations across North America.

And if you’ve been feeling downtrodden lately with politics, planting for pollinators and advocating on their behalf is something positive that you can easily do to have a real impact. Remember that pollinators do not have a voice of their own—it is our responsibility to ensure that they are protected too.

So what can we do?

First, let’s start by creating pollinator habitats in our own gardens. And why stop there? Let’s start pollinator gardens at our community gardens, our schools, and push our town boards and administrators to incorporate pollinator habitat into town planning and landscaping. By creating these “corridors” of habitat, we can help protect pollinators.

We have created a list of our “Top 15 Pollinator Plants,” including their pollinator counterparts. And each day going forward, we will be releasing a brief profile on each of these plants for the duration of the Million Pollinator Garden Challenge which is being celebrated until April 28th. We mark the beginning with today’s profile of Lindera benzoin, or Spicebush. You can find that profile at the bottom of this entry.

In addition to actively creating pollinator landscapes, here are some more actions you can take:

- Talk to your local garden centers. That includes the Agways, Walmarts, Lowe’s, Home Depots in your area. It is really important that they hear from you, the consumer. Consumer power is strong in the corporate world. Businesses do listen when consumers take the time to air their concerns—especially if they hear from enough of them.

- Write to your editor. A short, to-the-point, well-worded letter is great for keeping pollinators in the news and in people’s thoughts.

- Talk to your garden friends and neighbors. Education is key, and when it comes from a friendly face, a message has a greater chance to have an impact.

- Following that line of thought, offer to lead a workshop with your garden club, 4-H or Scout Troop, or at the local library.

- Talk to your schools and get the teachers involved, if they aren’t already. Create a Pollinator Week. Have students raise butterflies in classrooms and plant pollinator habitat. The possibilities are limitless!

- Talk to your local Planning Board. Or better yet, join it! Become an activist for native habitat in all municipal landscaping.

- And finally, head to the Million Pollinator Garden Challenge website (http://millionpollinatorgardens.org) and

- Register your garden as a pollinator habitat

- Upload a photo of your garden. You will be asked to fill in some other necessary information

- Where you’re asked to indicate “Your Organization/Partnership Affiliation,” select “The Association for Garden Communicators.”

Most importantly, think outside the box! There are plenty of ideas we have not listed here—if you have an idea you did not see here, that does not mean you should not try it! Remember, the pollinators cannot advocate for themselves. They need your help.

Lindera benzoin (Spicebush)

A truly wonderful early bloomer, Lindera benzoin (Spicebush) is our first introduction to great pollinator plants. It is named for the scent of its leaves, that when crushed, emit a subtle aroma, as does the bark. Classified as either a shrub or small tree, Lindera is an understated beauty of the woodlands, blooming at the same time as the flashy forsythia, for which it makes an excellent substitute. The softer yellow flowers of spicebush are, like hollies, dioecious, meaning that only the female plants, after receiving pollen from male plants, produce red berries in the fall.

Lindera prefers moist soils, and is typically found in wetlands: in floodplains and alongside bodies of water. Though it can take full sun, it can only do so when the soil is constantly moist. It is ideally suited to shady, wet areas, and makes an excellent buffer plant for riparian zones. Because of their gentle branching form, they appear best as a landscape plant in groups of three or more.

A member of the Lauracea family, Lindera has been used historically for multiple uses. Known by names such as “spicewood” and “wild allspice,” Lindera has been used for medical, culinary, fragrance purposes. American Indian tribes used the leaves, twigs, and berries for medicinal teas, and soldiers during the American Revolution used the berries as a substitute for allspice. Lindera tea was even used during the Civil War as a substitute for coffee.

For pollinators, Lindera benzoin is very important. In the spring, early bees, flies and butterflies are attracted to the flowers, which bloom earlier than many other species. The autumn berries of the Spicebush also provide an important food source for squirrels and birds. The berries are high in fats, important fuel for migrating birds.

Because of specific chemical compositions found in Lindera, most mammalian predation is discouraged, but caterpillars are frequent visitors. The Papilio troilus (Spicebush Swallowtail) relies on Lindera: the butterflies lay their eggs on the leaves, which once the larvae hatch, they consume as they move through their lifecycle. A caterpillar with a lot of character, the Papilio caterpillar’s green skin blends in perfectly with Lindera’s leaves. Its most distinct feature are the “eyes”: large black markings that mimic the heads of snakes. The Papilio troilus has even been known to “rear up” in imitation of a snake when threatened.

As a landscape plant, Lindera benzoin is a fabulous addition to any garden: it is a very easy plant to grow, (provided it is sited in its ideal conditions of moist, wet soils), and provides early spring interest before most species come out. For that reason, it is also an important addition to gardens from the pollinator perspective; as gardeners, we have an opportunity to have a beneficial impact on the environment around us. Because there is a limited number of blooming plants at this time, planting species such as Lindera benzoin is all the more important for pollinators searching for food, and is something we can easily do in our gardens.

If you are interested in learning more about the history of Lindera, the Wild Seed Project has an excellent in depth post on their blog.

References:

“L. benzoin, northern spicebush.” New England Wild Flower Society. <https://gobotany.newenglandwild.org/species/lindera/benzoin/>

Johnson, Pamela. “Lindera Benzoin. Spicebush. Lauraceae.” Wild Seed Project. May 2016. <http://wildseedproject.net/2016/05/lindera-benzoin-northern-spicebush-lauraceae/>

Murphy, Cindy. “American Spicebush: An Understated Beauty with History.” Grit. May/June 2008. <http://www.grit.com/farm-and-garden/american-spicebush>

Sheets, Jason. “April Plant of the Month: Lidnera Benzoin, Spicebush.” New York Restoration Project. April 3, 2015. <https://www.nyrp.org/blog/april-plant-of-the-month-lindera-benzoin-spicebush>

“Field Notes from the Beiser Field Station: October 7, 2008.” Marietta College, Biology Department. <http://w3.marietta.edu/~biol/biomes/spicebush.htm>

Interview by EcoBeneficial (Video)

EcoBeneficial! is a business whose mission is to change the way in which we think about and manage our landscapes. EcoBeneficial! offers educational online content – articles, videos and podcasts – as well as a variety of services – presentations and workshops, commercial consulting, consulting for homeowners, and freelance writing.

Thanks to Kim Eierman of for interviewing us for some native gardening inspiration!